Painting technique

“Check the measurements!”

Ferdinand Hodler did not simply rely on his eye, he checked the measurements of his models and landscapes. And he used different copying methods so as to produce his paintings efficiently.

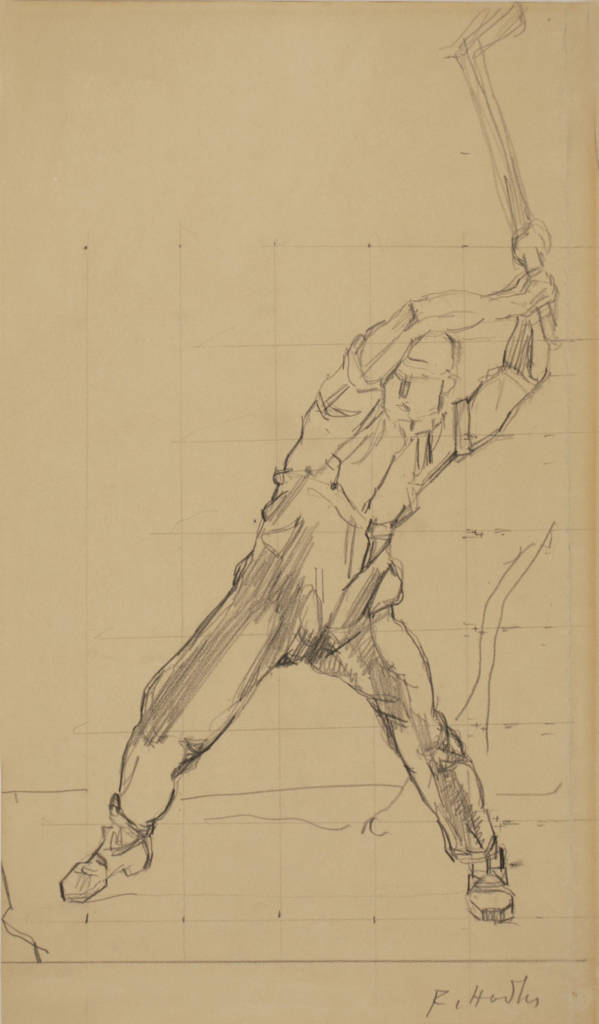

Ferdinand Hodler was meticulous in his approach to his motifs, after all, his main concern was to reproduce nature precisely. In the interests of his pictorial ideas he tried out and measured up several models. And he also urged his artist-colleagues to check the measurements. There is evidence that for The Woodcutter he tested a younger and an older worker.

“Hodler stood und front of a young lady in his shirt sleeves fidgeting with his compass … around her face in a way that could scare you.”

Johannès Widmer describing a scene, Widmer, 1919, pp 14–15

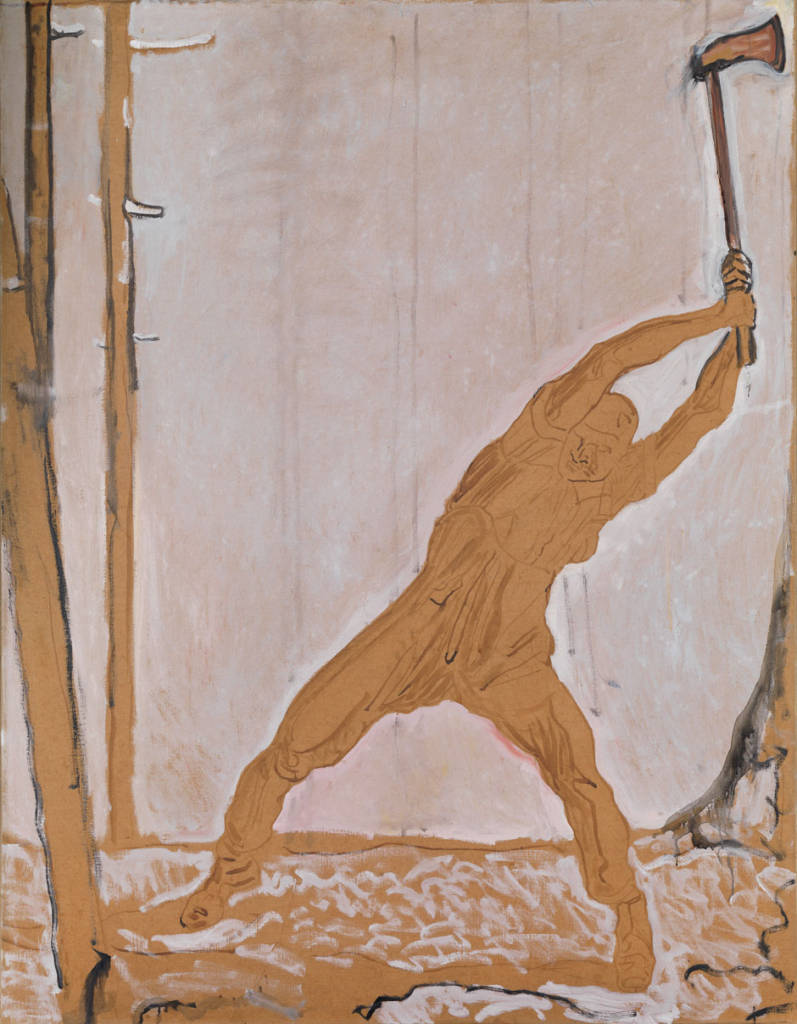

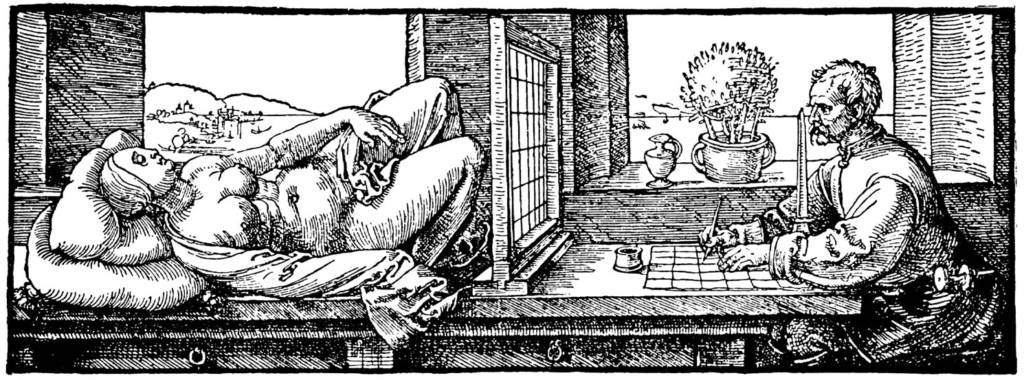

Tracing nature: grid frame

In order to capture a figure precisely, Hodler placed a frame spanned with a net out of cords in front of the model. With this he was able to transfer the figure to the corresponding line grid on the canvas or paper. In his view, that net frame was an important tool, and it has been described by several visitors to his studio. The line grid even remains partially visible in the finished painting and can be revealed by technological means. Ferdinand Hodler described his approach in a sketchbook. When asked by an artist-colleague how he had managed to depict a knight in the Marignano frescoes so well, he replied: “I depicted him through the net, millimetre by millimetre.”

An analysis of all the paintings as of the mid-1890s on which Hodler worked directly with a model show net frame lines, unlike the copies of a motif which he made by hand. To date however, no Woocutter painting has been examined technologically.

Enlargements: Transfer lines

Die Zeichnung in der Sammlung des Museo Villa dei Cedri ist ebenfalls mit einem The drawing in the collection of the Museo Villa dei Cedri also has a line grid. These are transfer lines used when transferring a motif from one painting to another, usually in a larger format. For example, alongside countless drawings and sketches of The Woodcutter there are three known formats which Hodler certainly transferred and enlarged in this way

Replication

When transferring a motif in the same size, as was often the case with The Woodcutter, Hodler also used tracing: he placed transparent paper on the picture and traced the figure. He then transferred the outlines to the ground coat of a new version, either by scoring it directly into the grounding, or copying it on the back of the tracing paper using graphite. Hodler also made a stock of tracings so as to be able to repeat a motif at will, in case the original painting was sold. His copies are painted differently to the respective initial picture in the series. The brushwork is swifter and more direct and aimed totally at the greatest efficiency. Yet Hodler did not distinguish between the first painting in a series and the subsequent ones. Often the second, third or tenth version even seemed better to him because it was done with greater control and he could learn from the earlier versions.

The special knowledge of the self-taught artist

ÜTransfer lines were also used by other artists in the 19th and 20th centuries, such as Robert Zünd or Cuno Amiet. Net lines, by contrast, used since the Renaissance to transfer nature onto a painting, were not customary for individual figures in Hodler’s day. As a painting tool, they violated the aspiration of an academic training in which nude drawing was practised extensively.

Hodler had not had that kind of training, but was familiar instead with copying processes. As a school pupil he already worked in his step-father Gottlieb Schüpbach’s workshop for decorative painting. Transfer lines were still customary in that profession up to the end of the 20th century.

During his apprenticeship with the veduta painter Ferdinand Sommer, Hodler copied landscapes by other artists. Sommer’s workshop strove for efficiency; production was almost factory-like, and later Hodler emphasised the simplification of the working methods as a positive feature. Hodler’s open and pragmatic handling of technical aids therefore, had to do with his personal experience. He considered the rejection of them to be false shame, “pompous” or “bluff”. In his view, they guaranteed precision and meant time-saving, which no artist should forgo.