Style

The Order of Things

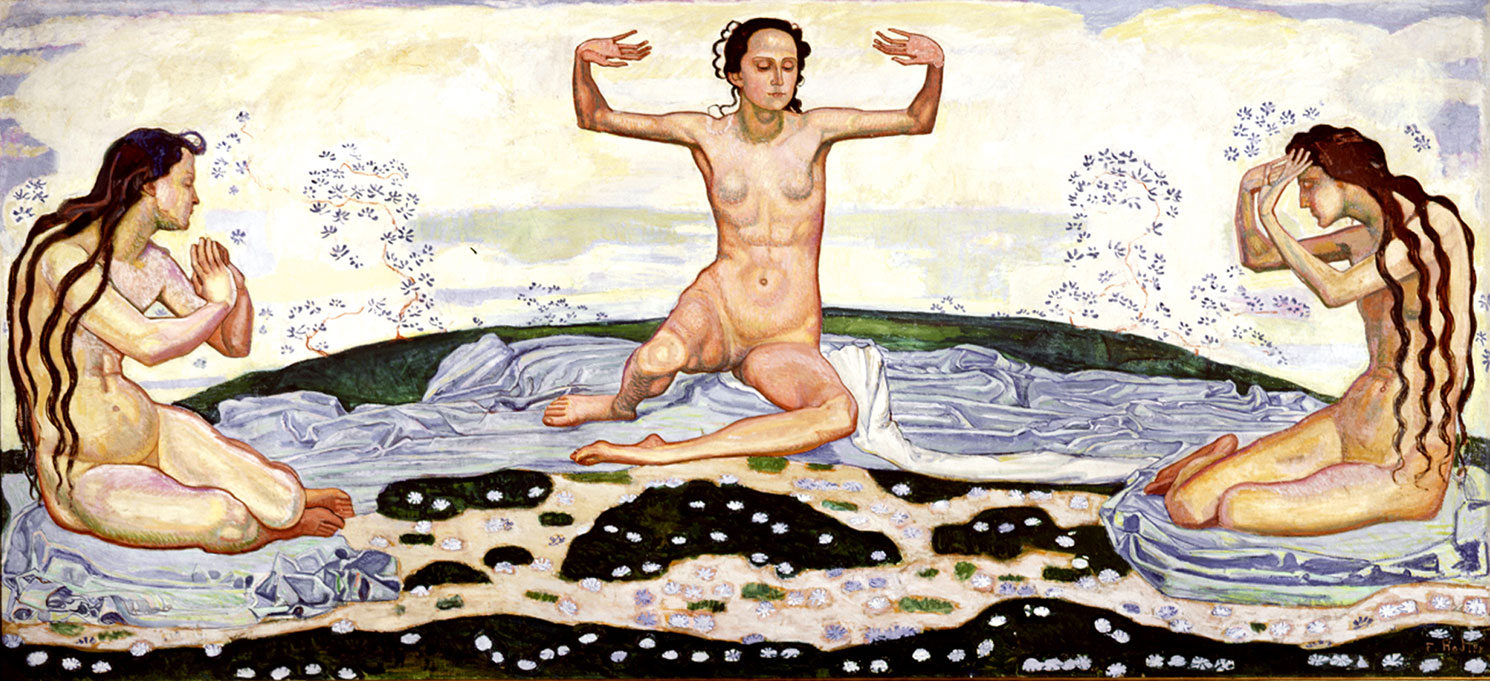

Hodler aimed to depict nature as precisely and recognisably as possible, while at the same time also revealing its inherent laws. For this he developed a painting style of his own: parallelism.

parallel worlds

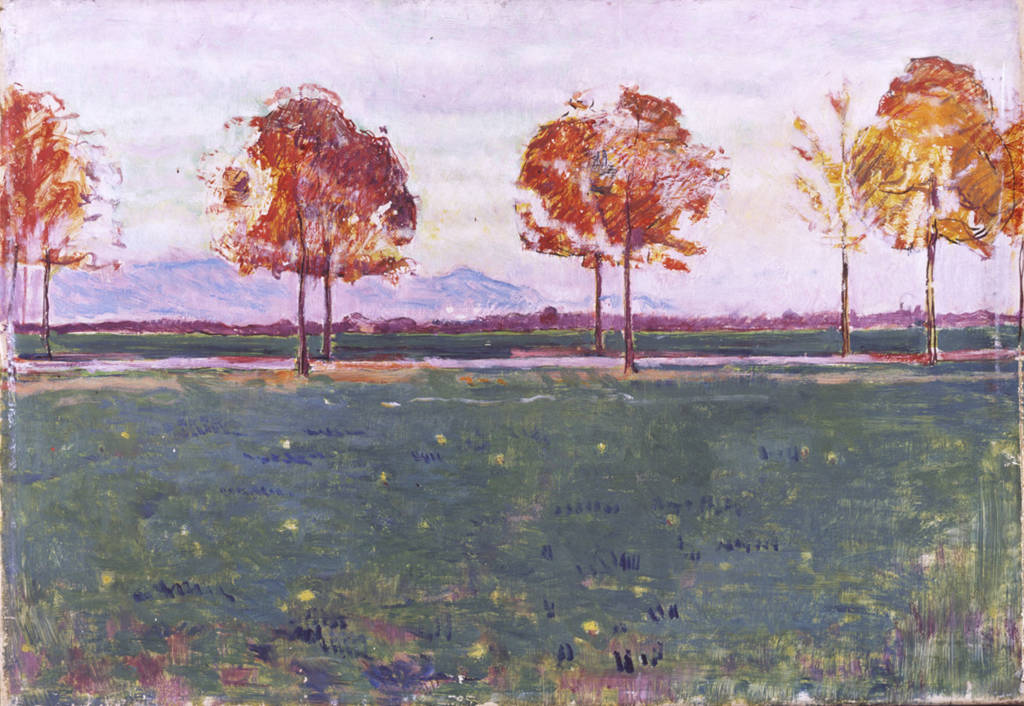

Hodler developed an order system of his own for his paintings which he called parallelism. Nature, for example, mountains, trees, clouds, flowers or figures, is depicted symmetrically in his work. This symmetry and the rhythmic pictorial elements it give rise to create an impression of harmony and equilibrium. In the Woodcutter this impression is achieved by the branchless parallel trees.

The Order

Ferdinand Hodler

The great effects of unity

In the midst of the sea by

Uniform sky

Death, what remains of immobility

Night, the extension of a

Similar element

The snow that unites

A snow covered tree

A large green meadow

A hill

A wide sky. The rainbow gives a great impression of unity.

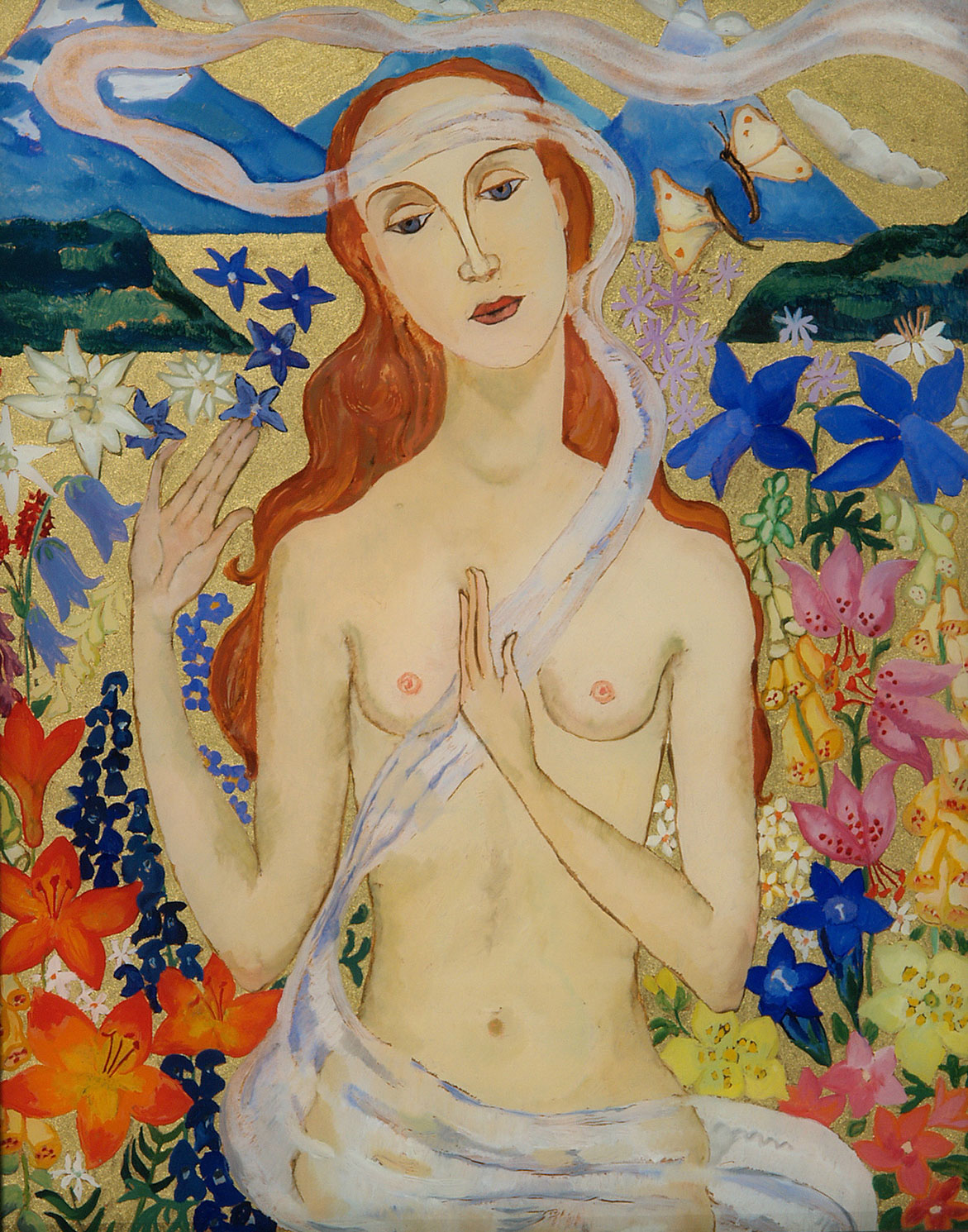

The task of art

As an artist Hodler saw his task as being «to give expression to the eternal element of nature, beauty». He did not paint his figures, objects and landscape as they actually are, but in keeping with his ideal. This approach is typical of Art Nouveau, which was the dominant style in art and architecture at that time. Art Nouveau was particularly appreciated by the wealthy upper classes because of its decorative aspects.

As regards the taste of his day, Hodler hit the nail right on the head. His aestheticising painting style and his linking of nature and beauty made him one of the important exponents of Art Nouveau.

Symbolism

Hodler’s aestheticising approach, which took a unity between man and nature for granted, contrasted with the reality of the artist’s own life. Around 1900 everyday life in Swiss cities was greatly marked by industrialisation. Yet in his paintings Hodler depicts neither factories nor urban scenes. His Woodcutter too is involved in a simple, non-industrial activity. The almost divine unity Hodler strove for in his art corresponds to the basic ideas of Symbolism. As art in the modern era no longer had a religious function, representatives of that movement sought a deeper meaning, an all-embracing truth, which Hodler also called the “world law”.